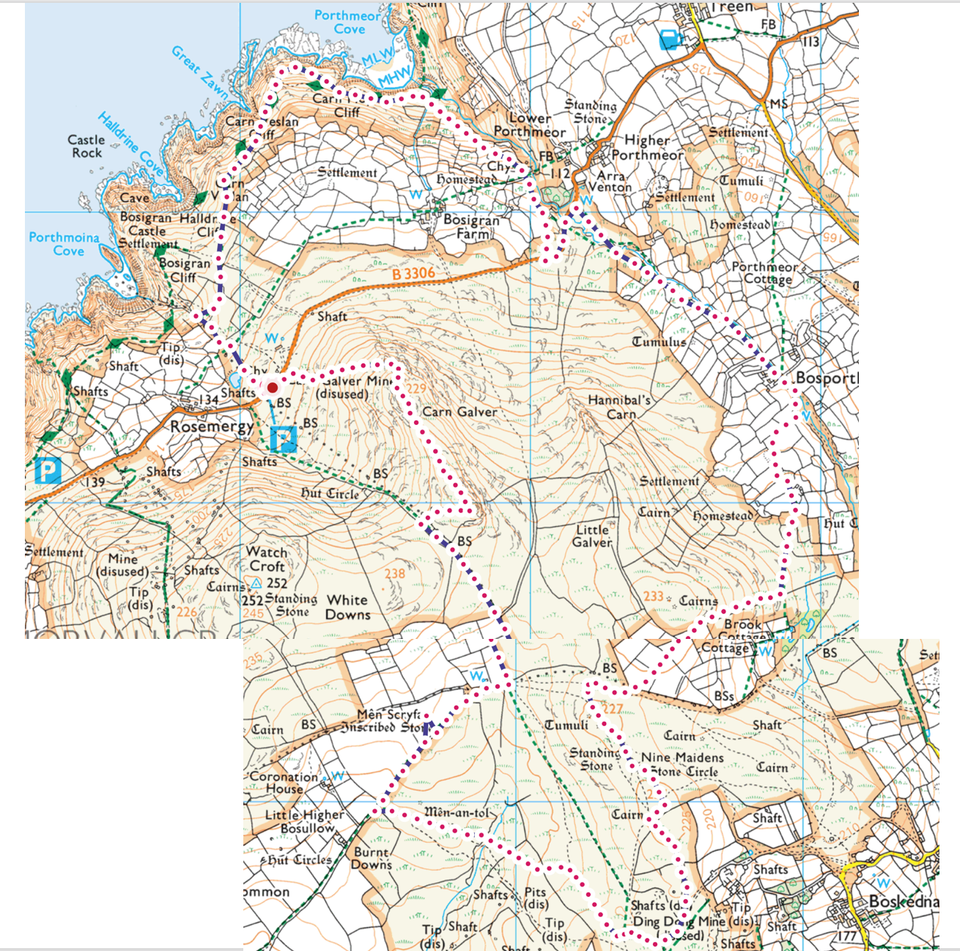

Penwith Moors

Distance: 10.3km

Ascent: 347m

Dec 2019 - Great to be back in the homeland and a Chistmas Eve squelch around the moors and coast. Stopped off at a few sites of interest. Lovely isolation. First was Lanyon Quoit. Situated in largely unpopulated and treeless Cornish landscape between Madron and Morvah, Lanyon Quoit, along with other Cornish dolmens, dates back to the Neolithic period (3500-2500BC), predating both the pyramids in Egypt and metal tools. The original use is somewhat disputed; some believing that it was the burial chamber of a large mound and others contesting that it was never completely covered, but rather used as a mausoleum and the imposing backdrop to ritual ceremonies, especially since it is believed that in its original form the quoit was aligned with cardinal points. Another theory is that bodies were placed on the capstone to be eaten by carrion birds. Parked at Rosemergy and climbed up to Carn Gulver’s summt, one of my favourite places to view the rugged north coast of Penwith. It was then first inland. Men Scryfa or Screfys (written stone) stands on high ground not far from Men-an-Tol. There’s an early Christian inscription on it which of course is of too late a date (about AD 500) to qualify it as a prehistoric site. On the granite pillar is inscribed RIALOBRANI CUNOVALI FILI. This signifies that the stone is of the Royal Raven, son of the Glorious Prince. The raven, a bird of carrion linked with death and the battlefield, was believed to have magical power for those who worshipped it; the bird was venerated over much of northern Europe, being an important symbol in an aggressive warrior society. The Men-an-Tol monument consists of four stones: one fallen, two uprights, and between these a circular one, 1.3m (4ft 6in) in diameter, pierced by a hole that occupies about half its size. An old plan of Men-an-Tol (the name means stone with a hole in Cornish) shows that originally the three main stones stood in a triangle, which makes certain astro-archaeological claims for it difficult to support. They could be the remains of a Neolithic tomb, because holed stones have served as entrances to burial chambers. Its age in uncertain but it is usually assigned to the Bronze Age. Traditional rituals at Men-an-Tol (centuries ago known also as Devil's Eye) involved passing naked children three times through the holed stone and then drawing them along the grass three times in an easterly direction. This was thought to cure scrofula (a form of tuberculosis) and rickets. Adults seeking relief from rheumatism, spine troubles or ague were advised to crawl through the hole nine times against the sun. The holed stone also had prophetic qualities and, according to nineteenth-century folklorist Robert Hunt: If two brass pins are carefully laid across each other on the top edge of the stone, any question put to the rock will be answered by the pins acquiring, through some unknown agency, a peculiar motion. It was then the wet task of trudging on to Ding Dong Mine. The name may refer to the 'head of the lode' or the outcrop of tin on the hill. In Madron church there is a 'Ding Dong Bell' that was rung to mark the end of the last shift of the miners. The stone circle at Boskednan consists of nine stone still standing and two fallen stones. Whilst the site is also known as the Nine Maidens or the Nine Stones of Boskednan it is likely there were originally 22 or 23 stones evenly space around the 69 metre (200ft) perimeter. The majority of the stones on site are around one metre in height. However, there are three stones on the northern edge of the circle that are considerably taller, measuring nearly 2 metres. Interestingly these taller stones line up with Carn Galver, one of the highest points on the West Cornwall moors. It would be likely that this had some significance. It is believed that Boskednan stone circle dates back to the early Bronze Age. Eventually, I made my way back to the coast where the wind was really up.